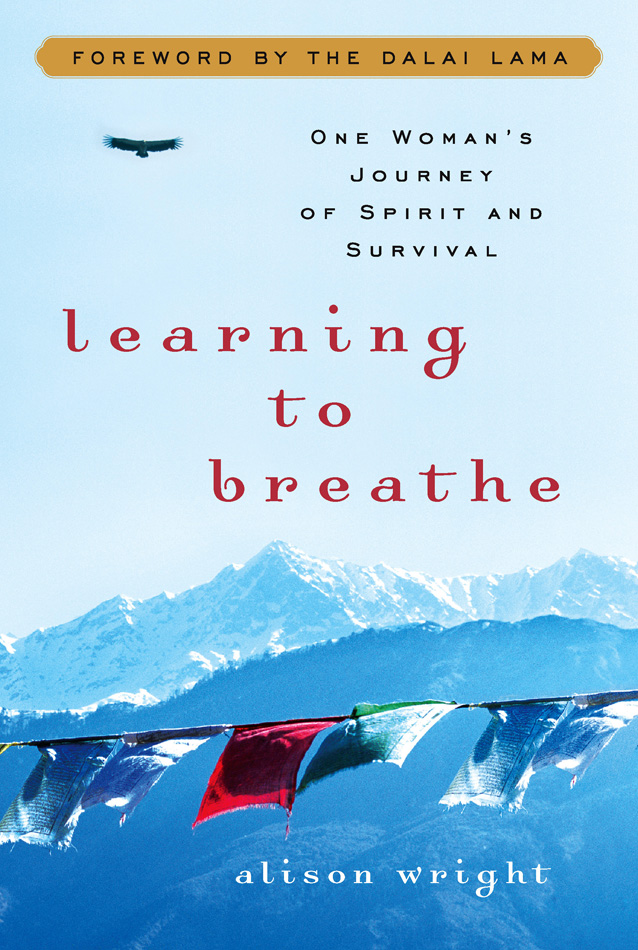

Each day that I spent writing my book, “Learning to Breathe, One Woman’s Journey of Spirit and Survival” was a reminder that I am alive because of the benevolence of strangers. This realization was what inspired me to start my foundation, The Faces of Hope fund. It was these strangers that encouraged me to want to give back in some small way to the people and communities that I’ve photographed in.

The Faces of Hope fund works with locally established and Non-Governmental Organizations to help provide fundamental health care and education to children and their communities globally. One of the initial projects of the Faces of Hope Fund was to partner with the non-profit organization Doctor to Doctor to help deliver medical supplies to the Kasi Clinic in Laos, which is mentioned in this book. I wanted to somehow repay the people there who had so determinedly worked to save my life that day on January 2, 2000.

Dr. Seng at Kasi clinic in Laos

I have never forgotten that I was saved by a small group of determined individuals who worked in a rural clinic with few resources–– sparse medical equipment and medications, and without sutures, phones, or even beds. My experience there has become a daily touchstone for me, motivating my work as I continue to travel around the world, photographing endangered cultures and documenting issues concerning the human condition. Through their generous time and donations, five physicians from the California-based Doctor to Doctor non-profit organization offered to accompany me to Laos: Dr. Robert Dolgoff and his wife Margarita, Kay Yamagata, Cynthia Nguyen, and Gregg Wheatland. In November 2008 the doctors and I set out for the Kasi clinic with $10,000 worth of medical supplies. Oliver Bandmann accompanied us as our translator.

Alison returns to Kasi, Laos

We drove the six-hour journey from Luang Prabang in a rented van––no bus for me this time! The roads are in much better condition than during my original journey, for which I was thankful, since there was unseasonal rain, which made the winding roads slick. In the dense fog, we could barely see the outline of nearby limestone mountains. Our driver expertly maneuvered his way along the switchbacks while slowly hugging the interior edges with care. We were all acutely aware of the dangers that this route held.

When we finally reached our guest house in the late afternoon we were greeted by what are now familiar faces to me. I jumped out to give a hug to Khamthat Chanthamougkhong, the young man who had stitched up my arm with nothing more than an upholstery needle and thread. He responded with his big shy smile. There was palpable excitement in the air as we were greeted by Dr. Seng and other town officials. We took them to dinner at the best- actually,the only – restaurant in Kasi. It was nice to visit together in a relaxed atmosphere and the beer flowed as we shared a toast. Kamthat, who only took a token sip, leaned over to me and whispered that it was the first time he had ever had alcohol.

The doctors and I receiving a baci ceremony at Kasi Clinic, Laos

The next day the doctors and I had our official visit to the clinic. In our honor the local staff wore clean white uniforms, which I had never seen before. Although the clinic had more employees than during my time here in 2000, it is still a very basic rural health center. There are still no proper beds or mattresses, screens on the windows, and extremely limited medical equipment. For example, if patients need an x-ray or any kind of lab work done, they are still sent five hours south by road to the capital of Vientiane. With Oliver translating, the U.S. doctors described exactly what the towering stacks of medicines we’d brought with us were for, while the nurses made notes and listened intently. Dr. Dolgoff gave me a packet of sutures so that I could personally hand them to Khamthat, the young man who had sewn up my arm so crudely, yet bravely, years before.

Receiving protection strings during baci ceremony

A local shaman was summoned to perform a back, a good luck-ceremony. Local villagers crowded in to watch the ritual through the open windows of the room. The baci, or su kwan, is a ceremonial “calling of the soul” and often celebrates a special event such as marriage, travel, a homecoming, a welcome, a birth, or an auspicious festival. Officials are honored by bacis, novice monks are wished luck with a baci before entering the temple and sometimes the sick are given bacis to facilitate a cure. The forces that are beckoned are considered to give balance and harmony to the body, or simply “vital breath.”

The American doctors, the clinic workers, and I all converged as a group with our arms around each other so that all our bodies were connected as one entity. As instructed, we touched an ornate silver dish. Its contents had been arranged by the elderly women of the village: a conical horn of shaped banana leaves, flowers, fruits, sweets, rice wine and white cotton threads. The shaman chanted Buddhist prayers and afterwards we each nibbled from the generous offering of eggs and rice. Rather reluctantly, the doctors and I sipped the harsh clear rice whisky, which burned my throat and made my eyes tear. The crowd laughed as I grimaced, encouraging me to swill the glass in one mighty gulp. I had no choice but to oblige. he shaman then tied white strings around each of our wrists. The white cotton thread, the color of peace and good fortune, is a lasting symbol of continuity, permanence and connection in the community. The baci ceremony calls the kwan, or souls, back to the body from wherever they may be roaming. Oliver explained to us, “It is an ancient belief in Laos that humans are a union of thirty-two organs and that the kwan watch over and protect each one of them. These kwan are mischievous and like to wander. The strings secure them in place, thus reestablishing an equilibrium.” We were told that the baci threads should be worn for at least three days and untied rather than cut off, although it is preferred that the strings be kept on until they fall off by themselves.

Khamthat Chanthamougkhong, Alison & Dr. Seng with “Learning to Breathe”

All the staff members in the room were insistent that each of them had to tie a protection string around our wrists, about thirty on each arm. By the end of the ceremony the doctors and I had each accumulated so many it appeared as though we’d had our wrists bandaged. The gratitude from the clinics workers was overwhelming and heartfelt, and we each felt deeply blessed.Especially me, given how I had once left this room on the near brink of death.

I shared the book I had written about my experience, although of course no one could read it. As it passed around the group, each one excitedly pointed at the photos of themselves or the clinic. The copy I had for them was dog-eared before we left. We had a discussion with the doctors and assessed what their other needs were. Topping the list was an x-ray machine.

Khamthat Chanthamougkhong, who sewed up my arm, celebrates by having his first ever drink of alcohol. He saves my life and then I corrupt him.

We then settled in for the impressive spread of local food that had been prepared in our honor for lunch. While munching a fresh spring roll, I mentioned that I had been looking for Alan Guy and his wife Van, who had driven me that fateful night from the Laos clinic to the Thai border. This couple had been so instrumental in saving my life and I had never given up hope of finding them. A young man gnawing on a piece of chicken mentioned that he had heard that Alan died last year, but he didn’t know how.

I put down my fork in surprise. I didn’t remember him being that old. It occurred to me if her husband had died, then where was Van? “Is Alan’s wife still in Laos?” I asked. “Oh, yes, she’s in Vientiane,” he told me, sucking the last of the chicken grease off each of his fingers. He wiped his hands with a paper napkin and pulled his cell phone from his pocket to make a call. For a moment I pondered the ease in which he did this. I thought back to how desperate I had been for that lifeline when I had lay dying here eight years ago. Then my heart began to race a little faster at the possibility that I was so close to filling in my final missing puzzle piece. I heard a faint female voice on the other end. When she was told a foreigner was on the phone, without missing a beat, right away Van asked “Alison?” We made a plan to meet in Vientiane.

The Doctor to Doctor non-profit organization in Laos:Dr. Robert Dolgoff

and his wife Margarita, Alison, Cynthia Nguyen, Kay Yamagata, and Gregg Wheatland.

Later that day the doctors and I poignantly said our goodbyes to everyone at the clinic, with promises to see them next time, hopefully with an x-ray machine. I hugged each person who I have now become so linked to over the years. The ribbons of white strings winding around my arms proved it. The doctors and I piled into our vehicle and headed south to the capital.

Van and I met the next day for lunch. I recognized her kind face and flowing long black hair; she was more articulate with her English than I remembered. She gave me a much appreciated photo of Alan, handsome and bearded, so I could remember what he looked like. She also presented me with an intricately woven black and white shawl that she had personally hand-made, a lovely gift. I gave her my book; she was surprised to see herself mentioned in it. I knew that she had already gone through major heartbreak- her only son had been killed on that same road shortly after my accident. I was shocked to hear that Alan had also been in an accident on that route, hitting another car in the fog. He died the following year after suffering injuries from the accident, complicated by newly diagnosed diabetes. Van was now living with her elderly mother, trying to recreate her life. This poor woman had lost both her son and husband to that road. Now we would always be bonded by it.

A reunion after eight years: Sirivan Keomany, who with her husband,

Alan, drove me from Laos to Thailand in the back of their truck.

Alan had died the previous year on November 7. Ironically, Van and I had been brought together on November 4. In Buddhist culture, the year anniversary of one’s death is a deeply respected milestone that is acknowledged by a feast including friends and family, and a ceremony surrounding a newly constructed spirit house. Both Van and I felt strongly that somewhere Alan had helped us to reconnect. While I never did get to buy Alan the beer I had promised him, I now had an opportunity to honor him in a different way. I humbly contributed some money to be a part of this ritual Van was organizing and wondered about how to begin thanking someone for saving your life?

Then I remembered a Chinese proverb. “We are all connected by a red thread,” I told Van. “This invisible thread connects all of us who are destined to meet regardless of time, place or circumstance. That red thread, may stretch or tangle, but it will never break. “Sometimes though,” I added with a laugh “the thread is white, and there are many.”

I held up my heavily decorated wrists to prove it.

Dr. Bunsom Santithamnont gives the thumbs up for “Learning to Breathe” at his

hospital in Udon Thani Thailand. He was also instrumental in saving my life.

Currently the Faces of Hope Fund is trying to get a much needed x-ray machine for the Kasi clinic.